This article dives into the core differences between MVPs and MMPs, breaking down when to use each, along with real-world examples—both good and bad. You’ll also get a five-step guide to building an MVP the right way and learn how to steer clear of the common pitfall of over-engineering your prototype. Thinking about outsourcing development? We’ve got you covered—contact us for expert advice.

Reading time: 23 min.

MVP and MMP aren’t just buzzwords in 2025—they are truly survival strategies.

Startups don’t collapse because of bad ideas. They fail because they scale too fast without proving those ideas work. Rushing ahead without testing means walking blind into operational failures, technical bottlenecks, and wasted capital. And once money and time are gone, they don’t come back.

Businesses, from lean startups to established enterprises, have learned this the hard way. The solution? Build small, test ruthlessly, and adapt fast. MVPs and MMPs aren’t just theories—they’re the best way to spot weaknesses early, back up decisions with real-world data, and turn ideas into viable, scalable realities.

At IntexSoft, we know this process inside and out. We’ve built, tested, and refined solutions that help businesses avoid costly missteps. In this article, we break down what MMP vs MVP really mean, how they differ, and why choosing the right one could define your success in 2025.

Keep reading—you’ll want to get this right.

We must acknowledge that too many businesses walk through our doors without clearly understanding what an MVP is or why it matters. They have ideas, ambition, and funding. What they don’t have is a tested foundation. And that’s where things start to crack.

The Minimum Viable Product is a practical tool for startups navigating always uncertain markets. It introduces a streamlined version of a product. Companies can attract early adopters, validate the idea’s worth and demand, and, importantly, secure investor confidence. This method offers learning before scaling.

History doesn’t lie. Facebook, Uber, Dropbox, Twitter, Aardvark, and Zappos started as MVPs.

Take Facebook. Zuckerberg didn’t launch a social media empire overnight. The first version was bare-bones, built with just enough functionality to test its core idea. No fancy algorithms. No sprawling features. Just a small release to a select group of users, gathering raw feedback before expanding. Look at the first version and compare it to what it is now.

As you can see, the contrast is staggering.

And that’s the point. A well-executed MVP isn’t the final product—it’s a proving ground. It tells you what is minimum viable product in agile development, whether an idea is worth real investment, and, more importantly, what needs to change before it scales. The companies that understand this survive. The ones that don’t? They disappear.

Take Airbnb. In 2007, Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia in San Francisco had an idea: rent out air mattresses in their apartment to help pay rent. Instead of sinking money into a full-scale platform, they built a basic website, tested demand, and proved people would pay to stay in a stranger’s home. That crude MVP exposed the real opportunity—short-term, peer-to-peer rentals. Without that test, Airbnb might not exist today.

MVP helps innovative companies enter the market without burning through resources. If you’re asking, what is MVP Agile, here’s why it works:

And here’s the kicker—once you’re in the field of MVP, new problems, ideas, and opportunities surface.

Let’s define MMP.

The startup world moves fast. What worked yesterday is outdated tomorrow. And while “MVP” has been the go-to playbook for years, there’s another contender in the mix—MMP.

Minimum Marketable Product. The concept first appeared in 2003 in Software by Numbers. But it wasn’t just theory—companies like Amazon, Airbnb, Spotify, Uber, Instagram, Buffer, and Foursquare turned it into reality.

Take Spotify. In its early days, the company faced a major roadblock: streaming technology wasn’t there yet. The assumption was simple—people didn’t actually want to own music. They just wanted instant access. But that raised questions. Would artists and record labels accept the model? Could they even make it work with existing tech?

Instead of diving in blind, Spotify built a lean, testable product—fast streaming, minimal buffering, and legal agreements in progress. They released a controlled version to validate the concept, solve technical bottlenecks, and gauge industry response. The approach worked. Today, Spotify dominates.

An MMP finds the balance between a bare-bones test and a viable, sellable product. It combines the best of MVP and MLP (Minimum Lovable Product)—a version that doesn’t just function but resonates.

Whats an MMP? Knowing when to leverage this type of prototype is truly worthwhile. Here, you can explore key points:

MVP is the rough draft, and MMP is the finished pitch. Get them mixed up, and you either spend too much before knowing if an idea works—or launch too soon and crash before you can take off.

Learn more details through the table below.

| Factor | Minimum Viable Product | Minimum Marketable Product |

| Purpose | Test a concept. The goal is to see if the idea has legs before investing too much. Early feedback shapes the next steps. | Enter the market. This isn’t just about proving an idea—it’s about making an immediate impact and getting traction. |

| Features | Stripped down. Only the absolute essentials make the cut. Anything extra is a distraction. | Refined and polished. It may not have everything, but what’s there is market-ready. |

| Target Audience | Early adopters and testers. People willing to try something unfinished and give honest feedback. | A broader audience. These are paying customers who expect a seamless experience. |

| Success Metrics | Learning and validation. The question isn’t revenue—it’s whether the idea is viable. | Adoption and revenue. If people aren’t using it (or paying for it), something’s off. |

| Risks | Misinterpreting early data. If the wrong conclusions are drawn, the whole project can go sideways. | Going to market too soon. A half-baked product will burn credibility fast. |

Consider MVP as a stress test. A way to see, early on, if your concept holds water or if it’s just another exercise in wishful thinking. Here’s how you do it—step by step, no illusions:

This is where too many startups stumble out of the gate. They get fixated on features, aesthetics, and the so-called “user experience”—but never stop to ask the fundamental question: What problem are we solving?

The only way to answer that? Cold, complex research.

First, market research. Who else is in the space? What’s already out there? What’s working? More importantly—where are the weak spots? The best businesses are built on gaps in the market.

Next comes customer research. Numbers first—quantitative data. Surveys, online forms, phone interviews. Get the raw stats. Then, dig into the qualitative side. Real conversations. Focus groups. Watch how people behave, not just what they say.

And if you intend to dig deeper, you’ll do secondary research, too—pulling insights from public records, industry reports, and university studies. The whole landscape is black and white.

Here’s a reality check: your product isn’t for everyone.

Most startups fail because they misunderstand their target audience. According to a CB Insights report, 35% of startups shut down because there was no market need for their product. They built something no one wanted.

Who are you developing for? Who will pay for this?

Companies that understand their audience create buyer personas—data-driven profiles of their ideal customers. A study by HubSpot found that using detailed personas makes websites 2–5 times more effective and improves email open rates by 14%.

Here are the most essential questions about the behaviors and motivation of potential users:

Take, for example, Google Glass Enterprise Edition—a billion-dollar project that flopped. Why? They were built for tech enthusiasts but marketed to the general public. The average person didn’t want to wear a futuristic headset publicly, and privacy concerns pushed adoption further away.

Most startups overbuild. They assume they need AI, blockchain, 15 integrations—before they even have a single paying customer.

This is the fastest way to burn money and lose focus. The data backs it up: 29% of startups fail because they run out of cash—often due to bloated development cycles and unnecessary features.

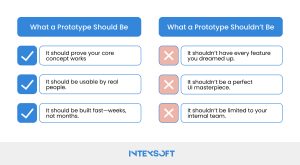

As we mentioned at the beginning of the article, your MVP is about testing the core functionality with real users as quickly as possible.

What’s the absolute minimum functionality needed to prove this thing works? What’s the one feature that solves a real problem? What can be built in weeks—not months? Everything else? Noise.

In 2007, Dropbox didn’t start with a fully built product. Instead, they launched with a 3-minute explainer video demonstrating how seamless file syncing would work. The result? 75,000 signups overnight—without writing a single line of code. This validated demand before they built anything.

Adding too many features too soon is called feature creep, and it can kill even promising startups.

Now, build a version that genuinely works. This isn’t the time for polish. It doesn’t need to be beautiful. It doesn’t need to impress investors. It needs to do one thing well.

Your friends won’t tell you the truth. Your colleagues won’t either. You need strangers. People with zero stake in your success.

Why? Because real users will find the flaws. They’ll break things. They won’t care about your vision—they’ll care about whether it works for them.

People don’t “discover” products. You make them impossible to ignore. If your launch flops, it’s not bad luck. It’s bad execution. The first 24 hours on platforms like Product Hunt determine whether you fade or explode. Be ready.

Build. Ship. Break. Learn. Repeat. A prototype isn’t an end product. You’re testing whether people want it, whether they’ll use it, and whether it actually solves the problem you think it does. The first version won’t be correct. That’s the point. Let real users poke holes in it because that’s how you know what’s real.

What comes after a prototype is collecting feedback and iteration.

Most founders listen selectively. They latch onto praise and dismiss the hard truths. That’s how bad products stay bad. If more than one user flags the same issue, it’s not an outlier—it’s a flashing red light.

Watch what users do, not just what they say. Click-through rates, heatmaps, churn numbers—these don’t lie. Customers will say they love your product right before they abandon it. Trust the data.

Every complaint is a free roadmap. If customers keep running into the same problem, fix the damn problem.

Here is some advice to follow:

It’s a trap that’s snared more than a few startups—the obsession with perfection. The MVP, in theory, is about speed and efficiency. In practice, it often turns into a bloated mess, packed with every conceivable feature. The result? A delayed launch, wasted money, and a product no one asked for.

This isn’t a new phenomenon. In our article, we have pointed out several unsuccessful examples. The brightest one is the Google Glass Enterprise Edition. But there is more than that.

Look at Quibi—a $1.75 billion lesson in overbuilding. The short-form streaming service banked on cutting-edge tech and a massive content budget, but it never answered the simplest question: Do people actually want this? The market said no. The company collapsed in six months.

The flip side is just as dangerous—stripping the product down to the point where it’s unusable. A “minimum viable product” still has to be viable. A bare-bones prototype that doesn’t let users complete their journey isn’t an MVP. It’s a mistake.

The key? Ruthless prioritization. Every feature should earn its place. The first version needs to solve one clear problem—and solve it well.

Each update should be deliberate. New features should remove friction, not create it. If they don’t improve the experience, they don’t belong. That’s how companies build products that last.

As you transition from an MVP to an MMP, there are several key factors that can make or break your project. In this article, we’ll focus on three of the most important ones. Pay close attention, as these can greatly influence your success or failure.

Emotional design taps into feelings of joy, excitement, and satisfaction, keeping users engaged. Think of the last app or device you loved. Chances are, it didn’t just work—it made you feel something.

Think about Apple. Their devices don’t just work well; they make people feel good. That sense of pride? It’s powerful. When users form an emotional bond with a product, they stay loyal. They come back. Again and again.

While emotional design creates a connection, a great user experience makes sure your product is easy to use and navigate. As you move from MVP to MMP, it’s crucial to remove anything that slows users down. Slow load times? Confusing menus? Unclear instructions? Fix them. Every friction point you eliminate makes the product better. The smoother the experience, the more likely users are to stick around—and turn into loyal customers. Keep it simple.

As you move to an MMP, usability also can make or break your success. You want users to be impressed—and more importantly, to stick around. Usability testing uncovers issues that could frustrate potential customers.

Understanding the MMP meaning is key: it’s about refining your product beyond the basics to deliver a seamless experience. Many apps started with clunky navigation and confusing listings. User feedback changed that. Now, they are global giants. Small tweaks. Big impact.

The reality? There are no fixed rules. The path from idea to execution is littered with cautionary tales—founders who overbuilt, under-tested, or ignored the warning signs. Some saw an opening, stripped their product down to its essential core, and got it in front of users before the competition knew what hit them.

Speed matters, but so does direction. An MVP is a test balloon. An MMP is a bet on a more refined product. Both have their place, depending on the risk appetite, the funding, and, most importantly, the patience of the founders behind them.

If you’re considering outsourcing the development of early versions of your projects, IntexSoft expert advice is always available. Contact us now.